Volunteers for Assisted Migration & Rewilding

of Torreya taxifolia

under whose shade you do not expect to sit."

— Nelson Henderson

Torreya taxifolia, America's most endangered conifer tree, is on the brink of extinction in its "native range" in the Florida panhandle. Paleoecological evidence suggests that T. tax would be native to northern Florida only in the peak cold times of a glacial advance, such as occurred some 15 to 20 thousand years ago. Since then, as interglacial warming has occurred, native range for T. tax should have been moving north, well beyond the "pocket refuge" of Florida's Apalachicola River Bluffs and northward into the southern Appalachians and Cumberland Plateau.

Because T. tax specimens that were planted on private estates in western North Carolina 90 years ago are thriving (and continue to produce, on their own, healthy recruitments), it can be argued that the southern Appalachians should be the destination for assisted migration of T. tax in today's climate. This argument for action is based on a strong biodiversity ethic: plant T. tax where it will thrive.

Land stewards near Waynesville, North Carolina, stepped forward

|

View or download in PDF articles pro and con assisted migration for Torreya taxifolia, which appeared as the featured Forum in the Winter 2004/2005 issue of Wild Earth:

|

| CAUTIONARY NOTE TO POTENTIAL PARTICIPANTS IN THE ASSISTED MIGRATION OF THIS ENDANGERED TREE: Just in case genus Torreya is able to cross-pollinate between its distinct species that have been geographically isolated from one another in the wild for millions of years, please do not plant any Torreya taxifolia seeds or seedlings in proximity to either the California species (T. californica) or any of the Asian species (the latter of which are widely available in commercial nurseries). Please keep them miles apart. Genus Torreya is wind-pollinated. And even though this species is ostensibly dioecious (an individual produces either male or female reproductive structures), there have been reports of individual Torreya trees violating this rule. So caution is advised.

As well, if you own property west of the Mississippi, do not attempt to grow Florida Torreya there. Biodiversity advocates generally advocate to keep America's eastern species of genus Torreya well isolated from wild stands of the native (and threatened) western species (Torreya californica) — which may ultimately need to migrate northward into Oregon in the decades ahead. (There is paleoecological evidence of genus Torreya in Washington state.)

This cautionary note applies, as well, to any growers who would like to assist with the other conifer "left behind" in the Appalachicola peak-glacial refuge of the Florida panhandle: Florida yew (Taxus floridana). Do not plant this endangered tree near other yew species, if you wish its seed to be useful for conservation purposes. |

||

The Fossil Record

The biodiversity argument for assisted migration can be supplemented by an understanding drawn from deep time: T. tax was found in previous eras in what is now North Carolina.

Torreya is a member of the ancient gymnosperm family Taxaceae, whose ancestors were evolutionarily distinct from other conifers by the Jurassic, nearly 200 million years ago. Because Torreya pollen is indistinguishable from the pollen of yews (Taxus), bald cypress (Taxodium), and cypress (Cupressus), known fossil occurrences of this genus are limited to macrofossils (seeds, leaves, and secondary wood), and these are sparse. There are no known Cenozoic fossils of Torreya in eastern North America. The most recent macrofossils identified as the genus Torreya in eastern North America are upper Cretaceous, and these were unearthed in North Carolina and Georgia.

Click above for three magazine articles written about our early "rewilding" actions.

Because worldwide climate during the Cretaceous was much warmer and far less seasonal than that of today, it is not surprising that Torreya macrofossils of Cretaceous age have also turned up along the Yukon River of Alaska. In western North America, there is Cenozoic fossil evidence of genus Torreya in the John Day region of Oregon (lower Eocene) and variously in California (Oligocene and late Pleistocene). Today, the genus is highly disjunct. Torreya californica survives as a rare tree, locally abundant in a score of isolated populations within the coastal mountains of central and northern California and on the west slope of the Sierras. It favors moist canyons and mid-slope streamsides, growing beneath a canopy of taller conifers and deciduous trees. Torreya nucifera is found in mountain habitats of Japan and Korea, and three other species of genus Torreya inhabit mountainous regions of China.

Recruiting Private Land-Owners

As explained in the Saving Torreya section of this website, a lot of effort is being expended to attempt (1) to preserve the few trees that remain in the wild in Florida, (2) to clone genotypes for safe-guarding in "potted orchards" in various botanical gardens, and (3) to replant progeny from the potted guardians in or near Florida native habitat. These three actions are taking place under the auspices of a legally sanctioned recovery plan for this endangered species, as administered by the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service.

The official recovery plan is not, however, the only approach available. So long as private seed stock is the source, there is nothing that prevents any landowner from planting Torreya taxifolia on his or her private property.

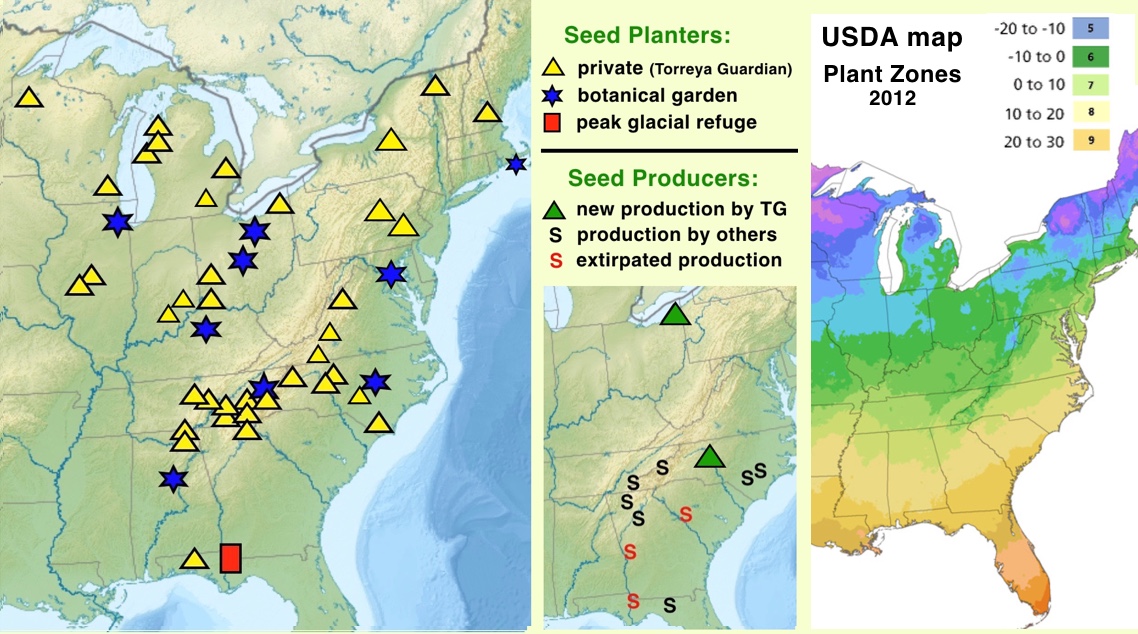

MAP of SEED PLANTERS: As of 2018, Torreya Guardians has donated seeds or seedlings to RECRUITED PLANTERS on private properties in 12 states. BOTANICAL GARDENS receiving seeds through Torreya Guardians include: Morton (IL), Secrest* and Dawes* (OH), Yew Dell (KY), Corneille Bryan* and Raulston (NC), Birmingham Botanical (AL). Note: * indicates videos of Torreya in these gardens can be accessed on our video page.

STATE-BY-STATE photo-rich webpages of our most successful plantings:

• North Carolina

• Tennessee

• Ohio

• Georgia

• Florida

• Michigan

• New Hampshire

We are happy to keep updating the list of institutions and landowners interested in obtaining seed for purposes of propagating and ultimately rewilding T. tax. Lee Barnes (Waynesville, NC) will be leading the development of guidelines for planting, nurturing, and monitoring the plants, aiming toward scientifically useful test plantings in a variety of natural forested landscapes. We will also be soliciting ideas and volunteers (including teachers who would assign projects to students) to work with private landowners in the very important task of monitoring over the course of decades:

(2) what ecological effects (for good or ill) ensue from this species addition to natural ecosystems

(1) which latitudes, site conditions, forest types, and propagation techniques best serve

To DISCUSS MAKING YOUR PRIVATE FORESTED LAND AVAILABLE FOR TEST PLANTING OF T. TAX contact either:

Proposed STANDARDS FOR ASSISTED MIGRATION can be viewed on-screen or downloaded in PDF:

Click here for an illustrated guide to CALIFORNIA TORREYA habitat preferences, which will aid in determining best sites for planting Florida Torreya seeds for assisted migration.

This is the mythic story to inspire all of us — conservation biologists, forest managers, and involved citizens — to pull ourselves out of despair over the looming impacts of climate change and get on with the great work of planting (and moving!) trees.

Lee Barnes is a founding Torreya Guardian, with the longest tenure of work with Torreya taxifolia. From 1981-85 his graduate research entailed advanced propagation techniques for three endangered plants in Torreya State Park of Florida — Torreya among them. Here Lee speaks of his research and his early role in securing Torreya seeds from Biltmore forest historian Bill Alexander for distribution to volunteer planters, primarily in North Carolina and various botanical gardens. (16 minutes on youtube)

Because this website is dedicated to Florida Torreya, it will be up to someone else to launch a website to chart the actions of a growing list of individuals attempting to help this needy (but still un-listed) species.

LEFT: A small grove of Florida yew is flanked by a low-growing palm species in Florida's Torreya State Park

Asa Gray, from his book Darwiniana, wrote:

• Distinguishing Features of Florida Yew, from Journal of the Botanical Research Institute of Texas, vol. 1, no. 1, 2007; page 226

The Florida yew, which differs by the abaxial leaf surface having a broader marginal area of nearly rectangular epidermal cells with less prominent papillae, occurs in northern Mexico and in the panhandle of Florida. In Florida it is found not much above sea level on bluffs and in ravines along 15 miles of the Apalachicola River in a mixed evergreen forest of .... In northern Mexico, it occurs between 2000 and 2500 m, which is at lower elevations than generally reported for the typical variety.

Award-winning animated video excerpts the allegorical tale by French author Jean Giono, 1953.

2016 VIDEO: Early history of Torreya Guardians (by Lee Barnes)

The Florida Yew is also found only along the Apalachicola Bluffs of northern Florida. Yew trees do not show signs of serious disease, so they are not nearly as imperiled as T. tax, but it is no longer reproducing very well in its "native range." If Florida yew was, likewise, "left behind" in its pocket refuge as the glaciers retreated, then it too deserves to assisted in "rewilding" to points north.

LEFT: close-up of the reddish, smooth bark of an old Florida yew, and a line of yew trees in front of what may be an old, fallen Torreya tree.

In 2018, Paul Camire researched online and published his findings in pdf of historic records of FLORIDA YEW horticultural plantings beyond its native range in northern Florida.

"Moreover, the Torreya of Florida is associated with a yew; and the trees of this grove are the only yew-trees of Eastern North America; for the yew of our Northern woods is a decumbent shrub. A yew-tree, perhaps the same, is

found with Taxodium in the temperate parts of Mexico. The only other yews

in America grow with the redwoods and the other Torreya in California, and

extend northward into Oregon. Yews are also associated with Torreya in

Japan; and they extend westward through Mantchooria and the Himalayas to

Western Europe, and even to the Azores Islands, where occurs the common yew

of the Old World."

Common name: Florida Yew

Distribution and ecology: N Mexico (Nuevo Leon, Tamaulipas, Veracruz), W Florida (rare, Apalachicola River; Chamaecyparis swamp ca. 8 mi SE of Bristol).

The Florida yew has allegedly retained the ancestral features of leaf epidermal papillae on the midrib, and the angular isodiametric epidermal cells (as seen in T-section), contrary to what might be expected for yew

growing in a seasonally hot and humid climate at relatively low elevations.... Perhaps there was not enough time for the Florida yew to have evolved significant morphological differences between the oscillation periods of climate change during the Pleistocene, or perhaps introgression has occurred between formerly distinct ecospecies, one found along the Gulf coastal plain and another in the upland areas. The overlap of key morphological features at the northernmost range of the species in Mexico would seem to indicate former contact in that region between two ecotypes, whereas the plants of limited occurrence in Florida are viewed here as relicts barely surviving instead of adapting to the present climate.