|

|

As of 2022, Lee Klinger is still using lime and other minerals to reverse California's epidemic of "sudden oak death". His business name: Sudden Oak Life. He desribes this practice as "fire mimicry" because it results in renewed health of struggling trees similar to the outcome of Indigenous forest tending by setting periodic ground-level fires. Both methods reverse the ill effects of bark and soil acidification. Liming is, however, the only option where the density of dwellings and the overgrowth of untended forests preclude attempting to use and control a ground-level fire.

LEFT: Torreya seedlings in the foreground, a moss covered log mid-ground, and moss-free young redwoods at the back. The grayish-green patches on those redwoods (and close-up below) are crusts of lichen. While lichens also acidify rainwater, dense mosses retain moisture much longer.

TOP RIGHT: Again, redwoods are moss-free, but their Big-Leaf Maple companions host so much moss that ferns are visible on the branches in the distance.

|

ABOVE: Young or fast-growing redwoods tend to show reddish bark. Redwoods in less favorable conditions tend to look gray-purple. Slowed growth reduces bark shedding — and thus crustose forms of lichens can accumulate. (Redwood branchlets on left; Douglas-fir on right.)

Return to top of CALIFORNIA TORREYA page

3H. Torreyas search for light gaps horizontally

Shade is so extreme in a northeast-facing deep ravine near the top of Diamond Mountain (northwest of Napa Valley) that many of the torreyas there had directed their main stems to search for light patches not by growing up but by growing outward — nearly horizontally.

|

|

It appears that a treefall episode pushed this torreya stem over — revealing not the roots but its "lignotuber".

The lignotuber size is proof that this stem did not arise from a seed. Rather, it began as a basal sprout arising from the lignotuber, possibly after a fire destroyed the previous main stem(s).

While this stem is rather young, the "tree" may be a century or more old.

The tree still lives so long as the rootstock remains healthy enough to continue sending forth replacement stems.

|

A torreya need not wait for a treefall in order to begin exploring its surrounds.

PHOTO BELOW: This moss-covered stem long ago initiated a downslope direction. The "seedling" near its base is almost certainly not a true seedling but a basal sprout. The tree's hidden lignotuber would easily have spread to this distance.

ABOVE: The next 5 photos will be different views of the same stem. Notice the white patch of missing moss on the top of this close-up of the stem. Then make sure you also see it in the rest of this photo sequence.

ABOVE: Notice the two sturdy stems growing vertically off the main leaning stem.

ABOVE: A closer view of a more distant section of the main leaning stem.

ABOVE: Even closer, but from a different camera view, such that 2 of the upright stems frame a cut redwood stump. The telephoto view also shows a living redwood at far left.

ABOVE: Another view, with the redwood stump and tall living redwood directly behind.

ABOVE: This is the final photo of the sequence, showing the full reach and plethora of skyward stems. (The white patch is easily visible.)

Return to top of CALIFORNIA TORREYA page

3I. Sun v. Shade leaf form adaptations

Torreya excels in adapting its leaf abundance and orientation in accordance with whatever amount of sunlight any particular habitat offers.

ABOVE LEFT: In its usual subcanopy position, Torreya grows leaves like a yew, genus Taxus, and both are members of the yew family: Taxaceae. (Sequoia National Park, 2005)

ABOVE: Torreya adopts more of a Douglas-fir leaf fullness and orientation when it gains access to unimpeded sunlight. Indeed, the long downward branchlets off the horizontal branches echo the growth form of Norway Spruce. (Yosemite National Park, 2005)

|

|

LEFT: Orientation and fullness are not the only features that vary greatly according to sunlight access. Even the needle length differs markedly. Advice: Beware of keys to species distinctions within genus Torreya that use leaf dimensions as an element.

BOTTOM LEFT: These seeds were developing in Yosemite National Park, full sun, on 19 May 2005.

BOTTOM RIGHT: The open edge of the forest at the Swanton station (north of Santa Cruz) had a female tree producing seeds in abundance. The seeds are much farther along in development because this is a month later (15 June 2005) and at an elevation only 50 feet above sea level.

|

SHADE |

FULL SUN (and heat) |

ABOVE: Don Thomas experimented at his home (San Jose, CA) with LEAF ADAPTATIONS in sunlight v. the usual subcanopy shade. September 2024 he sent the two photos. The distinctions are striking!

SEEDS ONLY DEVELOP ON BRANCHES OF FEMALE TREES THAT ACCESS SUFFICIENT SUNLIGHT.

3J. Torreyas excel within boulder fields (and along roads)

ABOVE & BELOW: These photos show the context of this remarkably lush torreya tree. This habitat is both a roadside and a boulder field created by roadbuilding into a steep cliff. Notice that the "tree" is actually multiple stems. Are they sibling basal sprouts of about the same age, growing from a torreya cut and cast down during roadbuilding?

Or did the torreyas on the upslope cast multiple seeds into this spot — perhaps before seed-loving rodents reoccupied the finished construction site? Or might a rodent have gathered the seeds and cached them here? Whatever the source, who but a torreya could establish seed in total shade and then grow at an angle before catching enough sun to straighten up and continue in glory?

BELOW: Two more sets of torreya trees with fast-growing, straight growth forms indicative of excellent habitat — thanks to the road-side boulder field.

ABOVE LEFT: View up the mountain while standing on the road. There is one small, brushy Torreya (center bottom of photo) where vegetation begins at top of road cut; blueish manzanita foliage is to its immediate right. The tall trees are California Live Oak and the short brushy shrubs are California Bay Laurel.

ABOVE RIGHT: Elsewhere on the upslope, we encountered a small torreya with the kind of shaggy bart indicating slow-growth and great age. Something other than shade is its challenge in this site. Perhaps the slope has been subject to too many slides or avalanches to have deep soil to retain snow melt. Notice that it got its start in the safety of rocks (albeit small rocks).

|

|

LEFT: This photo was taken by Jonathan Walton along a road above Los Gatos. (It is also posted at the top of this lengthy webpage.) The largest of all dozen stems visible is 72 inches in circumference.

"They are growing on a rather dry site with poison oak, California bay (laurel), madrone, Douglas-fir, and coast live oak. No redwoods in this area," he reports.

It would be fascinating to explore the bases to discern how many of them might share the same root system. Clearly, this set benefitted enormously from the boulder-making roadbuilding, followed by steadfast access to sunlight.

|

Return to top of CALIFORNIA TORREYA page

4. Site Visits by Connie Barlow to wild California Torreya groves

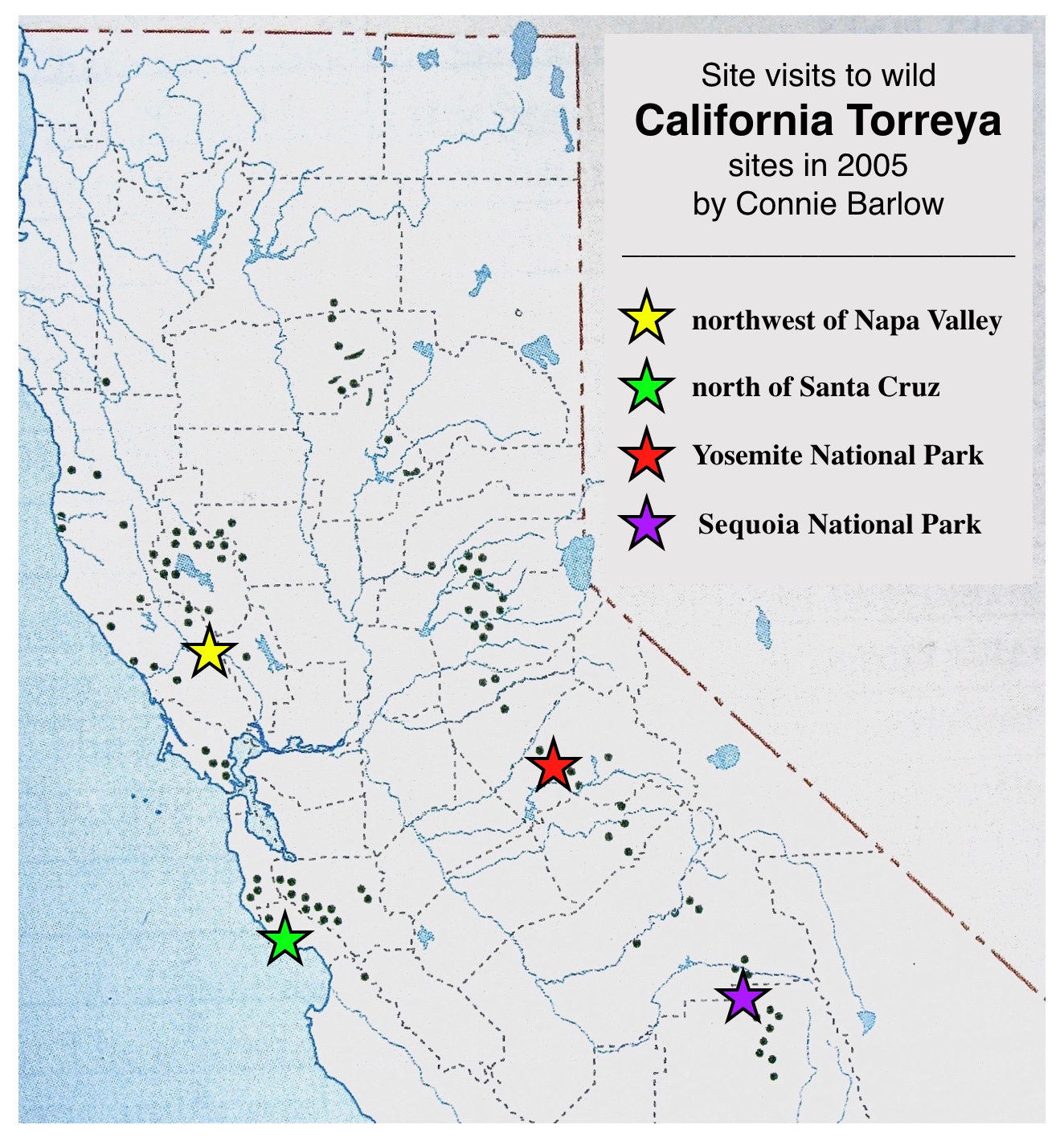

4A. Map of 2005 Site Visits

The map below uses green dots to mark the disjunct populations of California Torreya in the wild. All natural sites are in mountainous terrain, which affords this narrowly dispersed ancient conifer opportunities to track suitable microclimates by shifting altitude and local topography, along with shifts between northerly (cool) and southerly (warm) slope aspects or deep ravines and canyons while remaining on the same mountain. Short distance adjustments are crucial for this genus, as squirrels and humans seem to be the most active agents for seed dispersal.

|

|

• MAY AND JUNE 2005, I, Connie Barlow, (webmaster of this site and proponent of "rewilding" the endangered Florida torreya to the Appalachian Mountains) visited 4 distinct regions in which the California species of genus Torreya grows in the wild.

The map shows 2 sites in the Coast Range and 2 sites on the west slope of the Sierras.

My aim in 2005 was to observe California torreya trees in their wild habitats in order to provide guidance for volunteer planters of the Torreya species native to the eastern USA: Florida torreya.

Through photos, commentary, and video summary, those site visits help planters of Florida Torreya discern habitat preferences of the genus and thus pinpoint similar environments in eastern states for planting seeds and seedlings.

|

NOTE ON FLORIDA TORREYA: Because Florida torreya was left behind in its peak glacial refuge, Holocene warming had already restricted the species to cool ravines alongside the only river that drains the southern Appalachians through Florida on its way to the Gulf of Mexico. By mid 20th century, human-caused additional warming had made this species of Torreya so vulnerable to native diseases that reproduction halted. In 1986, the Florida torreya was listed as critically endangered. In contrast, because California Torreya did not have to leave its preferred mountain habitats during the Ice Age, it is not (yet) facing extinction. But with continued climate warming, it too may need human "assisted migration" in moving poleward.

4B. Narrated VIDEO by Connie Barlow of photos taken in 2005

during site visits to California Torreya trees

In 2018, I assembled my 2005 photos, along with relevant maps and other information into a 2-part video series, posted on youtube. My aim was to help other volunteer planters (and the officials implementing the Endangered Species Recovery Plan for Florida torreya) to "see" what this genus is capable of and its range of preferred habitats, such that the Florida species can be offered the best prospects for human-assisted migration poleward of its peak glacial refuge in northern Florida.

Part 1 (25 minutes)

Part 2 (27 minutes)

4C. Purpose of 2005 site visits

CONNIE BARLOW EXPLAINS: I visited these sites with the goal of getting a sense of the habitat and life association preferences of the California torreya, with the hope that this would give me (and others, via photographs here) a better sense of what the mountain habitat preferences for the "Florida" species (Torreya taxifolia) might be. In turn, this would improve our success rate when planting Florida Torreya into Appalachian Mountain sites and other northward locales.

|

|

The thesis is that Florida torreya (along with many other plants) migrated to Florida as the Ice Ages set in, but has been unsuccessful in this current interglacial in returning to the Appalachians from its "pocket refuge" in Florida. Its sudden failure to thrive and reproduce in its localized Florida habitat beginning in the 1950s supports this thesis, as does the fact that all other species of genus Torreya — in California, Korea, Japan, and China — live in mountain habitats.

My hypothesis as I began my California quest for Torreya was that direct access to mountains is the key reason that the California, Japanese, Korean, and Chinese species of Torreya are not endangered. I found that California torreya is indeed "rare, though locally abundant," as reported in the literature. I believe it is "locally abundant" because it has been able to altitudinally compensate for rises in temperature during this interglacial.

|

Its large seed, however, may be the reason that it is "rare". A large seed cannot waft on a breeze from one favorable habitat to the next. Rather, Torreya depends on squirrels to distribute its seed and thus to carry out the shifts in range (in contrast to other conifers, such as Douglas-fir and Redwood, whose seeds are easily airborne).

Possibly large tortoises and other creatures that are now extinct played important roles distributing torreya seeds in North America for millions of years prior to the end-Pleistocene extinctions, but today squirrels (and humans) are the only seed carriers who remain. This thesis is presented in "Bring Torreya taxifolia north now, by Connie Barlow and Paul S. Martin, published in Wild Earth in 2004. This article led to the establishment of Torreya Guardians, which in turn has led to substantial controversy about using "assisted migration" as a climate adaptation strategy for helping forest trees and endangered plants move their ranges in pace with climate change.

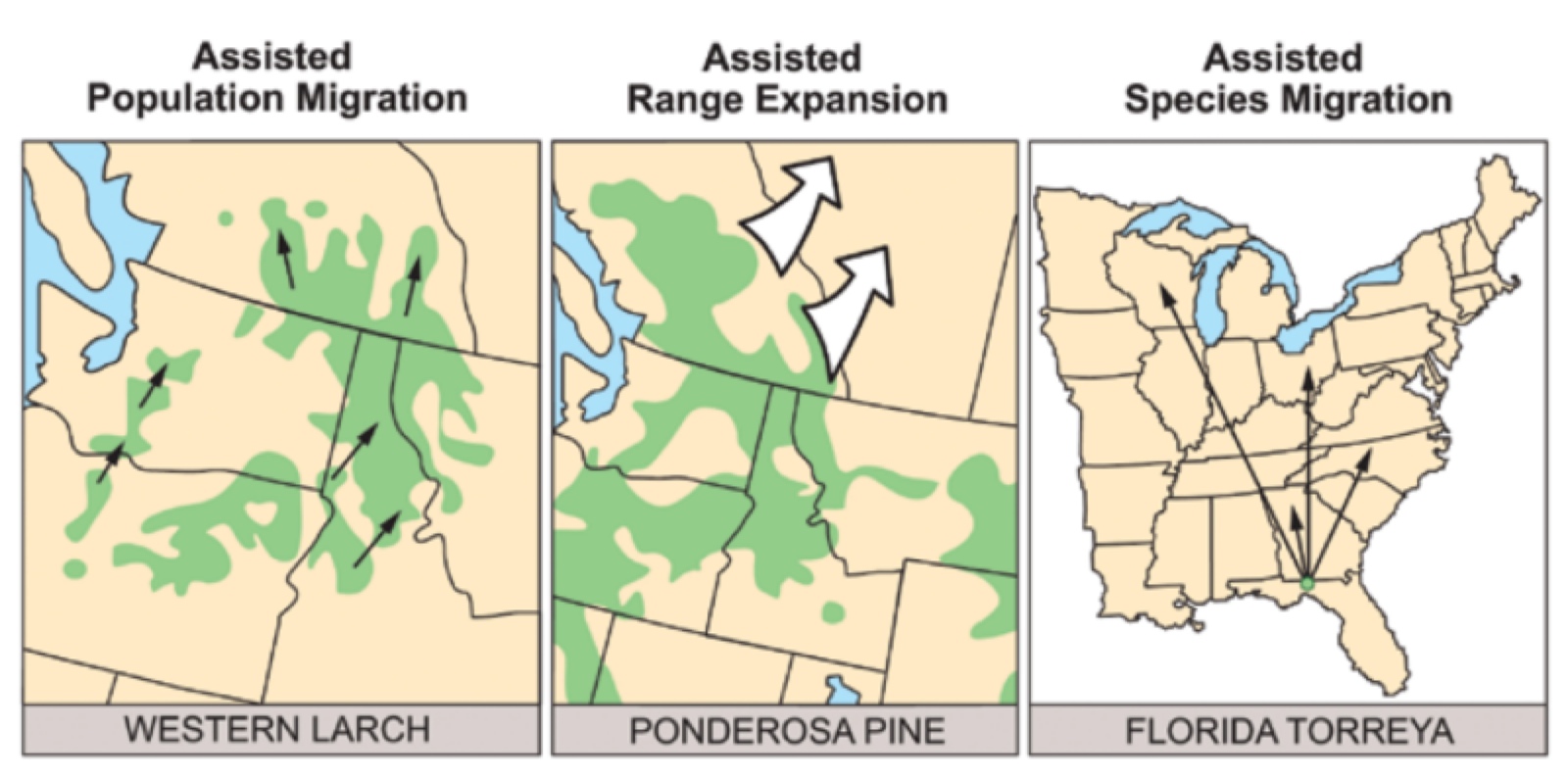

PAGE UPDATE: In 2022 Barlow updated this webpage (initially created in 2005) for a second purpose: There may be citizens on the West Coast who choose to collaborate in helping California Torreya track ongoing rapid climate change — and not simply by slow adjustment in altitude and aspect in its current mountain homes. Rather, there may be interest in "assisted range expansion" poleward.

|

|

Foresters make a 3-fold distinction in the types of assisted migration, with the "assisted species migration" (a.k.a. "species rescue") being the most radical.

The actions taken by Torreya Guardians made Florida Torreya the type-case example of the latter.

|

ABOVE: "Preparing for Climate Change: Forestry and Assisted Migration", by Mary Williams and Kasten Dumroese, 2013, Journal of Forestry.

Certainly there are already good reasons to engage in "population rescue" for geographic subsets of California torreya that have already topped out of their ability to move upslope. The Coast Range populations of California torreya that Barlow visited in 2005 had already reached their upslope and aspect (north or northeast) topographic limits.

Return to top of CALIFORNIA TORREYA page

4D. Site Visit Learnings and Hypotheses

Conclusions as of June 22, 2005 (by Connie Barlow)

NOTE IN 2022: The text below has not been altered since it was written. Barlow decided to archive the early results this way, and also because her conclusions have not changed.

1. SUNLIGHT REQUIRED FOR SEED PRODUCTION:

Genus Torreya thrives in sun, but in cool habitats, such as one finds at high elevations (4000 feet in the Sierras) or on the steep slopes of Coast Range ravines. Torreya seems to require access to direct sunlight in order to produce its large seeds.

2. STUMP SPROUTING AS A HOLDING PATTERN:

Although Torreya thrives in full sun, it can't expect to have it: other species easily overtop a Torreya. Stump sprouting, followed by stem dieback without reproduction, and then another round of stump sprouting seems to be a HOLDING PATTERN by which established rootstock waits out conditions too shady to support seed development. When Torreya is growing as an understory tree beneath a much higher canopy, it is simply waiting for the canopy to open by windfall, fire, or (on steep slopes) landslides. Immediately following such an event, the influx of sun allows the established rootstock to send a stem quickly upward, and (in females) to begin producing viable seeds, which disperse locally. The new seedlings may have an opportunity to establish in sunlight before the habitat returns to the deep shade of high canopy conifers or evergreen oak and bay laurel.

Repeated stump sprouting from established rootstock is all that remains of the once-locally abundant, though geographically limited, population of Torreya taxifolia in northern Florida. The easily observable difference between Florida Torreya resprouting and California Torreya reprouting is that the Florida species is plagued by stem cankers and by leaf browning that begins near the stem (not the branch tips). California Torreya growing in deep shade may assume a short and spindly growth form, but I saw no cankers on any trunk and only one instance of leaf death not associated with the natural shedding of old leaves as branches continue to lengthen. Indeed, when a Torreya tree is in full sun, its branches depart from the yew-like flatness and assume a bushiness that resembles Douglas Fir.

3. COAST RANGE CONSTRAINTS AND OPPORTUNITIES:

Genus Torreya is neither fast growing nor capable of producing a canopy as tall as that of competing trees that share its cool, Coast Range ravine habitats — notably Douglas Fir and Redwood. Thus, persistence of Torreya in the Coast Range seems to depend on Torreya's ability to linger in shady habitats (perhaps for centuries) as spindly, non-seeding trees that vegetatively replace their own dying stems by stump sprouting, until an overshading tree of a taller species happens to fall or a fire opens up the canopy. Acidification of soils and root rot may be the proximate causes of Torreya's failure in these situations to ever look like anything more than "saplings" (and droopy ones at that), and it is also the reason why stump sprouts can look quite healthy, because there is enough root to support very small growth forms, but not large ones. Thus, there is NOTHING WRONG with a Coast Range slope full of spindly Torreyas that grow under mature conifer forests with ground otherwise barren of understory vegetation — provided that every few centuries or so, fires revivify the soils or landslides open the canopy, at which time fresh stump sprouts enter a growth spurt and sexually reproduce, with some of the seed sprouting in places still favorable for successful development of rootstock, sufficient to weather out another shady period before the next slide or fire disturbance. In the wild, Torreya is thus adapted for spurts of sexual reproduction amidst long episodes of sexual quiescence.

4. SIERRA MOUNTAINS CONSTRAINTS AND OPPORTUNITIES:

Torreya also grows in steep ravines in the Sierras (as witnessed by the site I visited in Sequoia National Park), and there it is subject to the same constraints and opportunities as noted above. However, I also visited south-facing, steep dry slopes in which a canopy (of broadleaf, mostly evergreen oaks and laurels) was generally less than 30 feet tall, sometimes less than 20 feet tall. In these DROUGHT-STRESSED circumstances, Torreya has an opportunity to join others in the canopy as a sexually reproducing tree. Because the Sierra sites (unlike the Coast Range) are richly endowed with surface rocks and boulders, Torreya's LARGE SEED gives it a unique opportunity to germinate and establish in the shadow of rocks and boulders, eventually breaking through into sunlight.

5. THE SYMBIOTIC ROLE OF NATIVE AMERICANS

Because Torreya may require periodic fires to foster sexual reproduction as an understory tree, Native Americans may have played a symbiotic role in this tree's success. Active fire-suppression during the 20th century probably has been cumulatively detrimental, both in depriving Torreya of growth-spurt opportunities and through acidification of soils. My companion for the Santa Cruz area outing, Lee Klinger (his website for healing trees is "Sudden Oak Life" (www.SuddenOakLife.org), was convinced that the ancient Torreya specimens with gigantic trunk girths growing on the flat river terraces of Scotts Creek achieved such size only through the assistance of the Native inhabitants who may have favored Torreya for its big edible seed, just as they are known to have assisted oaks with edible acorns and redwoods that could provide shelter (in trunk bole caves created by intentional burning) and spiritual sustenance. In Scotts Creek watershed, we also found evidence that the Natives had "limed" the big redwoods, by depositing crushed shells at their base. For the very large Swanton Creek specimens, therefore, a continuation of the arborcultural assistance to which these giants have become accustomed may be a wise strategy.

NOTE: On 8 October 2005, the Garden Section of the San Francisco Chronicle published an article that features the ideas and ongoing success of Lee Klinger's "SUDDEN OAK LIFE" project, and thus the efficacy of using lime and other techniques to counter soil acidification that stresses mature trees and thus makes them highly susceptible to the proximate cause of "Sudden Oak Death": the fungal-like Phytophthora ramorum.

6. SUGGESTIONS FOR T. TAX ASSISTED MIGRATION:

Although the species of Torreya now struggling in Florida demonstrably can grow in shady conditions, it may be a wise choice in effecting "assisted migration" northward for planters to seek out sites of recent disturbance or treefall for planting seed, and then to assist the seedling by weeding out plants that threaten to overtop it. Steep slopes are ideal, and if you can find surface rocks and boulders, plant Torreya seeds amidst them, especially in places where plants that need sun for germination and early growth would be unable to grow. For the long-term, after rootstock is established, human tending should not be necessary, and the tree could rely on windfall, slope slumpage, and perhaps the rare fire to occasionally (geologically speaking) open up canopy for growth spurts and sexual reproduction.

Return to top of CALIFORNIA TORREYA page

6. Extracts from Other Web Pages on California Torreya

• General information: "http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/plants/tree/torcal/

• Local knowledge of Torreya californica:

http://www.tarol.com/torreya.html

[EXTRACT from the website]

Finding these trees requires a bit of knowledge. First of all, where to look? California Torreya grow amongst incense cedar and live oak in shady ravines and rocky gorges between 2,000 and 6,000 feet in elevation in the Sierra Nevada and slightly lower in the coastal ranges. I have found them growing in three nearby locations. The closest is about two miles up the Doyle Springs Trail near Camp Wishon in Sequoia National Forest. Next closest would be along the Crystal Cave Trail in Sequoia National Park. The third area is near Boyden Cave in Sequoia National Forest near Kings Canyon National Park. There, near the parking area, is a beautiful specimen, the largest I have seen!

Second, how do you identify this tree? At first glance its foliage looks like that of a white fir. Its needles are deep green, flattened, and 1-2 inches long. Their needles are aromatic and this has led to them sometimes being called a "stinking cedar." Their fruit is a modified cone, blue-green, plum-like, and about 1 inch long. They are small trees, rarely attaining heights of 60 feet and 2 feet in diameter. They grow slowly, however, so although they do not reach a great size, they can live to be several centuries old. Their branches are slender and they spread out making for a slightly ungainly appearance. Unlike other conifers, they are dioecious, meaning that there are separate male and female trees. The fruits hang from the tips of the outer branches from the female trees in late summer and autumn. Male trees produce pollen but never fruit.

Once you find a California Torreya tree you'll find it is adapted to its foothill environment. They can sprout permanent new trunks from their base when they are cut or burned, thus they are adapted to foothill fires. Their wood is durable and flexible and was used by Native Americans for making hunting bows. Their seeds were harvested and roasted for eating and their roots were used for making baskets.

• Other locations: http://www.botanik.uni-bonn.de/conifers/ta/to/californica.htm

[EXTRACT from website]

USA: California. Rare and local along mountain streams, protected slopes, creek bottoms, and moist canyons of the Coast Range and Sierra Nevada, at 0-2000 m elevation (Hils 1993). See also Thompson et al. (1999). Arno and Gyer (1973) indicate that it can be found in "draws and basins on Mt. Tamalpais in Marin County;" along "the road entering Yosemit Valley from El Portal" (Yosemite National Park); at "the entrance to Boyden Cave in Kings Canyon" (National Park); and "the trail to Crystal Cave and near Clough Cave in Sequoia National Park."

I have only found it in one location so far, on the road towards Giant Forest a few miles beyond the Foothills Visitor Center in Sequoia National Park. My notes report: "Here I find what is definitely the most prickly conifer I have ever encountered. This is a decent-sized little grove. They're growing amidst evergreen oaks, blue oaks, tanoak, a few small incense-cedars, and an understory with a xeric analogue of ladyfern, shrub oak, and probably poison oak. There's active regeneration, trees and seedlings growing both above and below the highway. Within 100 m of the sample point there are probably 50 stems taller than breast height, the largest being the one that I photographed the bark of, which has a dbh of about 25 cm. These trees are growing on a south- or southeast-facing slope. It seems to be a relatively dry microsite, but the torreyas are on locally concave topography. Slopes are 60-70%. We only find fruits on the largest, sun-grown specimen. Seedlings, of which the smallest I can find are about 15 cm tall, basically look the same as the larger plants except that their needles are shorter, about 1.5-2 cm vs. 4 cm on sun foliage in the mature trees." [photo: "californica2.jpg" caption=Tree in Sequoia National Park, CA [C.J. Earle, 24-Mar-01].

• More Locations and Plant Associations: http://reference.allrefer.com/wildlife-plants-animals/plants/tree/torcal/distribution-occurrence.html

[EXTRACT from website:]

California torreya is endemic to California. Its range has two distinct

parts: one in the Coast Ranges and one in the Cascade-Sierra Nevada

foothills. In the Coast Ranges, it is distributed from southwest

Trinity County south to Monterey County. In the Cascade-Sierra Nevada

foothills, it is distributed from Shasta County south to Tulare County

[8]. Although not rare, it is not an abundant species. Local

occurrence is widely scattered throughout its range [3], and trees are

often infrequent in these localities [8].

LISTED IN THESE ECOSYSTEMS. NOT OFFICIALLY ENDANGERED.

FRES20 Douglas-fir

FRES21 Ponderosa pine

FRES24 Hemlock - Sitka spruce

FRES27 Redwood

FRES28 Western hardwoods

FRES34 Chaparral - mountain shrub

KUCHLER PLANT ASSOCIATIONS :

K001 Spruce - cedar - hemlock forest

K005 Mixed conifer forest

K006 Redwood forest

K007 Red fir forest

K011 Western ponderosa forest

K012 Douglas-fir forest

K025 Alder - ash forest

K029 California mixed evergreen forest

K030 California oakwoods

K033 Chaparral

SAF COVER TYPES:

207 Red fir

213 Grand fir

221 Red alder

224 Western hemlock

229 Pacific Douglas-fir

230 Douglas-fir - western hemlock

232 Redwood

234 Douglas-fir - tanoak - Pacific madrone

243 Sierra Nevada mixed conifer

244 Pacific ponderosa pine - Douglas-fir

245 Pacific ponderosa pine

246 California black oak

249 Canyon live oak

HABITAT TYPES AND PLANT COMMUNITIES:

California torreya is plastic is its habitat requirements, and occurs in

many diverse plant communities. In the Coast Ranges, it grows in

chaparral and various coastal forests such as redwood (Sequoia

sempervirens). It is associated with canyon live oak (Quercus

chrysolepis) and California bay (Umbellularia californica) woodlands in

both coastal and inland foothill regions [10]. Inland populations are

most commonly found in the ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa) belt [3,8].

It is rare in chaparral communities of the Cascade-Sierra Nevada. It is

not a dominant or indicator species in community or vegetation typings.

LISTED AS A THREATENED SPECIES IN IUCN RED LIST

http://www.redlist.org/search/details.php?species=34026

Much of the population outside protected areas has declined. The species is relatively common in the Sierra Nevada but less so in the coastal ranges. The expansion of agriculture is mainly responsible for the decline.

• EXTRACT from 1973 book Discovering Sierra Trees by Stephen F. Arno (Yosemite/Sequoia Natural History Association).

Finding California torreya requires considerable knowledge of where to search and what to look for. The species reaches its best development on cool shady slopes and in canyons of the coastal mountains in Lake and Mendocino counties; it inhabits draws and basins on Mount Tamalpais in Marin County. Also, it grows in various rocky gorges and ravines scattered along most of the western slope of the Sierra Nevada between 2000 and 6000 feet elevation. Torreyas line the road entering Yosemite Valley from El Portal. Other good places to find them include the entrance to Boyden Cave in Kings Canyon, and the trail to Crystal Cave and near Clough Cave in Sequoia National Park.

In the south-central Sierra, torreya typically occupies rocky gulches too low and hot for Douglas-fir or areas beyond Douglas-fir's southern limits. In Sierra canyons, torreyas rarely attain two feet in diameter and 60 feet in height. Small size, coupled with their dense crowns, gives them a youthful appearance. Nevertheless, trees only 1 to 1.5 feet thick are likely to be two centuries old. Torreyas and coast redwood are notable among the world's conifers in their ability to sprout permanent new trunks from cut or burned stumps. In this respect, torreya, like the chaparral shrubs, is adapted to foothill fires.

Note: another source reports that California torreya "prefers moist, shaded, north-facing slopes (but found in open, sunny, exposed locations), usually near watercourses between 2,000 and 6,000 feet on the western slope.

• EXTRACT from the 1999 book Conifers of California by Ronald M. Lanner (Cachuna Press).

California nutmeg is an evergreen widley but sparsely scattered up and down the Coast Ranges and along the west side of the Sierra Nevada and Cascades. Never forming a continuous forest, but found rather as isolated trees or in small groups, the nutmeg is usually seen tucked into shaded ravines or rocky gorges, beneath a canopy of pines or other conifers. Where it is stunted by growth on serpentine soil, it is a shrub of the chaparral. But throughout most of its range it grows as a modest-size forest tree 30 to 50 feet tall. One giant near Fort Bragg in Mendocino county reached a height of 141 feet before it was illegally felled.

Habitat: California nutmeg is found on moist, rocky microsites within the shade of tall, coniferous forests; it grows as a shrub on serpentine substrate. It has a wide array of associates and ranges from about 2000 to 7000 feet.

Distribution: It grows in the Coast Ranges from southwest Trinity county to Fremont Peak in Monterey County. It is also found in the Cascades and Sierra Nevada, ranging from Shasta County south to Tulare County.

• USFS "Fire Effects" species page on Torreya californica contains useful information.- https://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/plants/tree/torcal/all.html

EXTRACTS: Male California nutmeg bear their microsporophylls within strobili. In contrast, the ovules of female trees are not contained within strobili but are solitary [16]. Male strobili begin growth the year prior to

flowering, while females trees develop ovules in one growing season

[21]. Torreyas are wind pollinated [16]. Male trees must normally be

within 75 to 90 feet (23-27 m) of female trees in order to effect

pollination [24]. Seed production is erratic. Good seed crops may be

followed by crop failure the following year [10]. Seeds mature in 2

years [19]. Being heavy, seeds usually fall near the parent plant; wind

dissemination is rare [17]. Seed predation by Steller's and scrub jay

is high [10]. Seeds require a 9- to 12-month stratification period

before germination [21]. In one study, seeds stratified for 3 months

before planting took an additional 9 months to germinate under

greenhouse conditions. Ninety-two percent of seedlings germinated at

that time. [15]. Temperature regimes during the stratification period

were not noted. Seeds sometimes germinate without stratification but do

so slowly [21].

Growth of trees in the understory is slow [10]. Sudworth [24] reported

trees from 4 to 8 inches (10-20 cm) in diameter were 60 to 110 years of

age, while those from 12 to 18 inches (30-46 cm) in diameter were 170 to

265 years old. The growth rate needs further study, however, as rates

of over 1 foot (30 cm) per year have been reported in cultivars [3].

Preliminary data obtained from tree-ring counts of saplings on the El

Dorado National Forest shows some trees attained heights of 4.8 feet

(1.5 m) in 28 years [10].

California nutmeg sprouts from the roots, root crown, and bole

following damage to aboveground portions of the tree [3,10,19]. Some

nutmegs reproduce by layering [21], but the layering capacity of

California nutmeg is unknown.

SUCCESSIONAL STATUS: California nutmeg is very shade tolerant [9] and is found in late seral

and climax communities [3]. Following disturbance such as fire or

logging, sprouts growing from surviving perennating buds appear in

initial communities [10].

Habitat types and plant communities: ... occurs in

many diverse plant communities. In the Coast Ranges, it grows in

chaparral and various coastal forests such as redwood (Sequoia

sempervirens). It is associated with canyon live oak (Quercus

chrysolepis) and California bay (Umbellularia californica) woodlands in

both coastal and inland foothill regions [10]. Inland populations are

most commonly found in the ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa) belt [3,8].

It is rare in chaparral communities of the Cascade-Sierra Nevada. It is

not a dominant or indicator species in community or vegetation typings.

• The Gymnosperm Database offers site-specific information:

Sequoia-Kings Canyon National Park: I have found it on the road towards Giant Forest a few miles beyond the Foothills Visitor Center. My notes report: "Here I find what is definitely the most prickly conifer I have ever encountered. This They're growing amidst evergreen oaks, blue oaks, tanoak, a few small incense-cedars, and an understory with a xeric analogue of ladyfern, shrub oak, and probably poison oak. There's active regeneration, trees and seedlings growing both above and below the highway. Within 100 m of the sample point there are probably 50 stems taller than breast height, the largest has a dbh of about 25 cm. These trees are growing on a south- or southeast-facing slope. It seems to be a relatively dry microsite, but the torreyas are on locally concave topography. Slopes are 60-70%. We only find fruits on the largest, sun-grown specimen. Seedlings, of which the smallest I can find are about 15 cm tall, basically look the same as the larger plants except that their needles are shorter, about 1.5-2 cm vs. 4 cm on sun foliage in the mature trees." I also have a report that they occur in Sequoia National Park on the lower part of the trail from Potwisha campground to Marble Falls (Roy Malahowski email 2011.03.13), and Arno and Gyer (1973) state it can be found at the entrance to Boyden Cave in Kings Canyon and along the trail to Crystal Cave and near Clough Cave in Sequoia National Park.

California coastal parks: Arno and Gyer (1973) indicate that it can be found in "draws and basins on Mt. Tamalpais in Marin County." Samuel P. Taylor State Park near Point Reyes has some very large trees, including two that were 30.25 and 32.3 m tall in November 2011 (Steve Sillett email 2011.11.19). The trees can also be found, at an unusually low, dry location, on the trails of Low Gap Park in Ukiah (Mark Hedden email 2017.07.10).

• CONNIE BARLOW finds info online re torreya in HENRY COE STATE PARK:

I googled Henry W. Coe State Park (near San Francisco), along with the word Torreya and then again with the word nutmeg, and thus came up 2 items that both speak of how north-facing slopes and canyon bottoms seem to be the habitats for mesophytic trees like redwoods and torreyas there. That is very important information strongly suggestive that this is southern-most range, and thus the populations of these trees will be threatened early by ongoing climate change:

• https://scv-habitatagency.org/DocumentCenter/View/125/Chapter-3-Physical-and-Biological-Resources

...The redwood forest land cover type is dominated by an overstory of redwood with a variety of associated tree, shrub, and forb species in the understory. This land cover type is uncommon in the study area, only occurring in the Santa Cruz Mountains in the west portion of the study area along creeks and valleys, generally on north-facing slopes. Stands of redwoods are found along Uvas (Uvas Canyon County Park), Llagas, and Arthur Creeks. Most redwood forests have been logged since the second half of the nineteenth century, and most of the existing trees are stump sprouts. However, in many areas, particularly along creeks, dense cover of redwood trees has been maintained. Areas that were burnt following logging now support chaparral or oak-dominated communities. Redwood forests occur in areas that receive substantial rainfall, generally more than 35 inches per year. Common plants associated with these forests include trees such as tanoak, madrone, and California bay; the shrub layer include species such as hazelnut (Corylus cornuta var. californica), thimbleberry (Rubus parviflorus), and black huckleberry (Vaccinium ovatum). In riparian areas, California bay and bigleaf maple are common, California nutmeg (Torreya californica) may occur, and ferns such as sword fern (Polystichum munitum) often form a dense layer....

• https://coepark.net/images/pineridgeassociation/ponderosa/Summer_2021.pdf

... The final conifer is the very uncommon California Nutmeg. It grows mostly as individual trees or in small groups and is found from Fremont Peak north through the coast ranges and in the middle elevations of the Sierra Nevada. At Coe Park, they have only been found on the north facing slope above the East Fork Narrows and in a few canyons on the east side of Blue Ridge. Most of the plants on Blue Ridge probably burned in past fires. The good news is that they stump sprout. The trees, up to about 50 feet tall, have bright green needles with needle-sharp tips. The green oblong fruit apparently reminded early botanist of the fruit of the unrelated tropical nutmeg plants....

• In Bija-Rim Forest, KOREA: http://www.lifeinkorea.com/Travel2/cheju/225

[EXTRACT from website]

This forest contains 2,500 Torreya nucifera, aged 300-600 years old, and is said to be the best area in the world for this single species of trees growing so densely together. Because the trees are evergreens, people can enjoy the dense forest all year long. Several rare parasitic plants grow within the trees. The trees blossom around April and fruits ripen in autumn. The fruits are widely used for medicinal purposes and food. The quality of the wood is excellent and is used for high-class furniture and stone checker boards.The Pija tree has been designated as Natural Monument #374 for protection.

A natural nutmeg grove (Torreya nucifera community) on Mt. Hallasan (designated Natural Monument #384), extends over 448 thousand square meters. One of the few natural nutmeg groves in the world, it contains 2,570 trees ranging fromn 500 to 800 years of age. They measure from 7 to 14 meters in height, 0.5 to 1.4 meters in diameter (measured a meter from the ground), and 10-15 meters in width at the crown. In the past, nutmeg was valued as vermicide and its wood was popular for high quality furniture and paduk (go) boards for the wealthy. The area is also noted for many rare orchids which grow naturally. These include Nadop'ung-nan (Aerides japonicum Reichb. fil.) P'ung-nam (Neofinetia falcate hunb Hu), K'ongjjagae-ran (Bulbophyllum drymoglossum Maxim.), Huk-nanch'o (Bulbophyllum inronspicuum Maxim.), and Pija-ram (Sarcochilus japonicus, mig.)

"The New Millennium Nutmeg":

This 813-year old tree inhabits this nutmeg grove. It is the oldest nutmeg in Korea and the oldest of all evergreen trees on Jeju Island. This tree is a witness to the indomitable spirit of Korea's ancestors in overcoming hardships imposed by the environment and isolation, and was named the "New Millennium Nutmeg." Local residents wish the spiritual power of this noble tree to bring everyone happiness, prosperity, and health in the coming millennium.